Why does peer-to-peer lending exist?

The core observation that drives WeFinance and every other peer-to-peer lending platform is that the savings rates offered by banks are (substantially) below the interest rates charged by those same banks to borrowers. By making the transaction direct at a rate between these two values, both sides can, in theory, benefit.

Of course, the calculation isn’t actually that simple. There are risks involved in lending, you can’t use your money as freely when it’s lent to someone else, and work is involved on both sides in maintaining a loan. If the alternative for would-be peer-to-peer lenders is less risky, then it makes sense for them to sacrifice some interest; or if there is a lot of work involved for either side, they might choose to pay a little more or earn a little less.

So it makes sense that there is some gap between these two numbers…but how big should that gap be? You could probably write several dissertations with theories on that topic, considering a variety of factors. But one quick-and-dirty way to see if things might be out of whack would be to look at how these values vary over time. If the gap now is very different than it used to be, and we don’t have a good clear justification for that, that might suggest that one or both of the rates aren’t set efficiently (though we can’t say for sure whether they were set inefficiently now, in the past, or both).

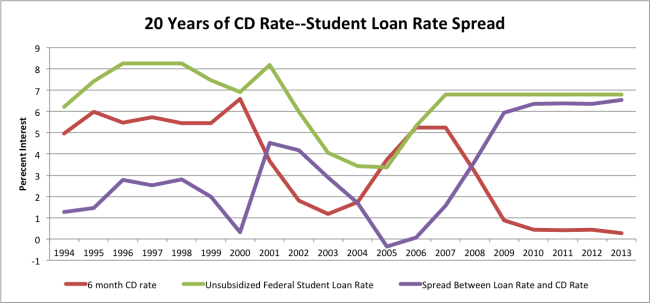

There isn’t just one ‘savings rate’ and people pay a variety of amounts on their student debt depending on a variety of factors. But, for the sake of concreteness, I looked at the federally maintained 6-month CD rate compared to the federal unsubsidized student loan rate for the last 20 years. (There are a variety of subsidized options that have varied over the years, but this is the unsubsidized you would pay on debt for, say, a graduate degree.)

(Sources: federalreserve.gov, New America Foundation)

So, even though student loan rates today are as high as they were in the 90s, the spread over the savings rate is more than twice what it was 20 years ago. As the early recession of the early 2000s brought CD rates down, student loan rates came with them. Later in the decade, both values recovered together, with the student interest rate lagging slightly. In fact, if you were going to grad school in 2005 and could pay for it out-of-pocket, you would still have been better off taking a loan voluntarily and putting that money straight into a CD that paid more with no real risk (since you could always pay the student loan off early as soon as the CD rate came down). The notion of taking out a loan for the heck of it has got to be hard to believe for someone who took out student loans in the last few years.

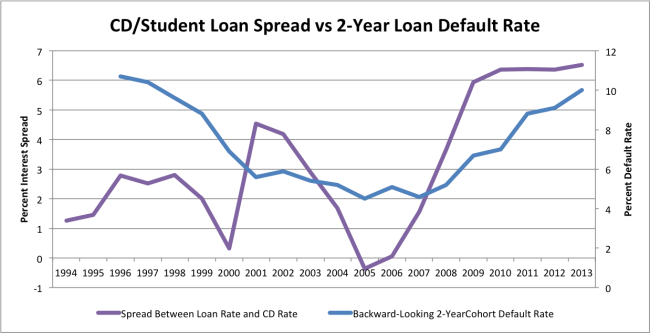

This isn’t an ironclad analysis by any stretch, of course, as many other factors could play a role in why these rates are set as they are. In terms of costs of loan maintenance, you’d probably expect those to fall over time as more information and transactions can be done online, so that doesn’t sound like a great justification. What about the risks involved? If the default rates were up, it would make plenty of sense for loan interest rates to stay high even when savings rates dropped.

(Sources: federalreserve.gov, New America Foundation, Department of Education Office of Federal Student Aid)

Unfortunately, this is not an apples-to-apples comparison, as the rate spread applies to graduate loan rates in recent years, and the loan default rates are across all loans. Furthermore, since we don’t have as much data on whether more recent loans will default than we do about older loans, the best available comparison is against the percentage of loans that defaulted within 2 years after repayment began (so the 2013 data point is the share of loans that started repayment in 2011 that had defaulted by 2013). But, from this quick view, it certainly doesn’t look like the savings/loan rate spread nicely correlates with default rates: although default rates have risen since 2008, they’re still below what they were in the mid-90s, when the spread was at its lowest.

Why do you think this spread has been so high for so many years?